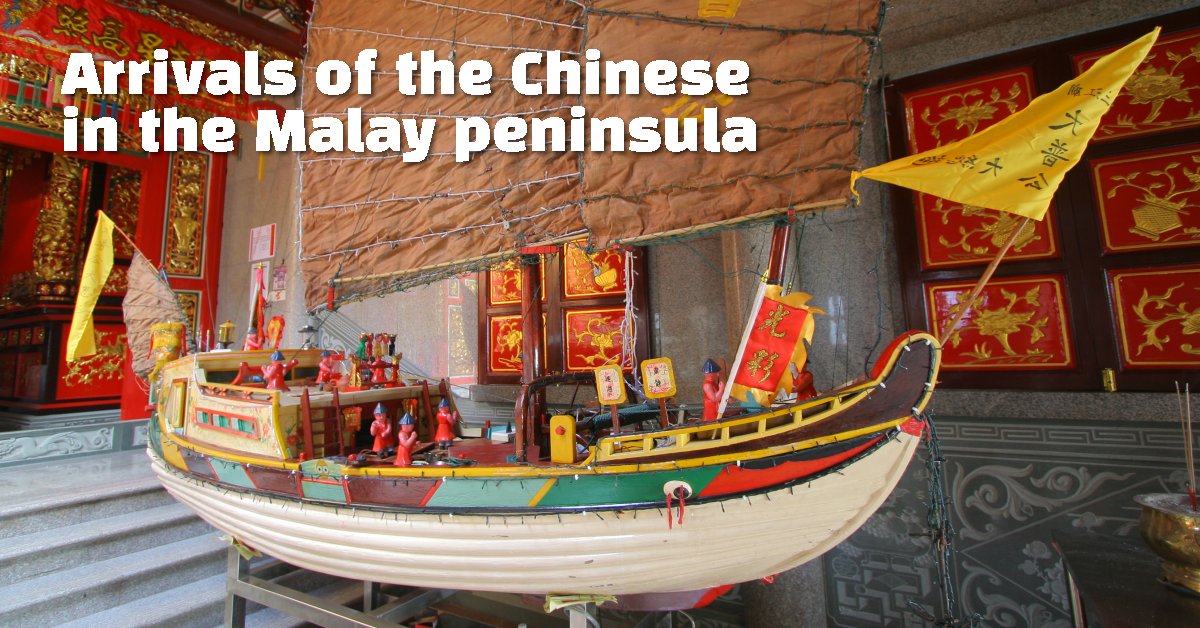

Replica of a Chinese junk, similar to those that brought the Hui'an Hokkien people from Fujian Province to faraway Nanyang (22 December 2006)

Replica of a Chinese junk, similar to those that brought the Hui'an Hokkien people from Fujian Province to faraway Nanyang (22 December 2006)

The arrivals of the Chinese in the Malay peninsula* can be explained as having occurred under three major waves which I shall call Wave 1, 2 and 3. This is a hypothesis that I form based on studying the lingua franca of the Chinese in Peninsular Malaysia, and determining why in some cities, there are Chinese communities that speak Baba Malay, in other cities, there are two different types of Hokkien spoken, while in yet others, Cantonese predominates.

I hypothesize that the first two waves of Chinese settlers experienced periods of total isolation, when their interaction with their parent homeland, China, was completely severed. This explains their level of assimilation, and hence the number of loanwords in their vocabulary vis-à-vis that of later arrivals. In contrast, those arriving under Wave 3 enjoyed an unbroken link with China, until such time that they assimilated into the local society.

(* The scope of this article covers the western coast of the Malay peninsula. I have not yet researched on the origin of the Chinese on the east coast, which I expect is related, nor those in East Malaysia.)

Fujian was the main province in China that provided the bulk of immigrants, particularly of Waves 1 and 2, while Guangdong provided a substantial number in Wave 3. The provinces of Hainan, Guangxi, Jiangsu and Zhejiang also contributed immigrants in smaller numbers.

In relation to this article, read also Where does Penang Hokkien come from.

Statue of Admiral Zheng He, Malacca (9 July 2005)

Statue of Admiral Zheng He, Malacca (9 July 2005)

Arrivals of the Chinese of Wave 1

15th centuryThe founding of a Malay sultanate in Malacca (1400-1511) greatly enhanced economic activities between Malacca and the surrounding regions including China, particularly its southern provinces. Being an entrepôt, it attracted merchants from Sumatra, India, Burma and of course, China.

In an age without trains, planes or automobiles, the Chinese merchants depended on wind propulsion to get them to Malacca, where they would remain for a few months until the monsoon changes direction to return them to China. The return voyage is call tnui1 Tng3 Snua1 (this article uses the Taiji System of Intonation for Penang Hokkien), meaning "return to China", and the merchants called themselves Tng3 Lang2, meaning "Chinese", or literally "Tang people", in reference to the Tang Dynasty. This same term tnui1 Tng3 Snua1 is later used by the Wave 3 immigrants for a different meaning.

Scrolls in the Peranakan Tun Tan Cheng Lock's house (2 May 2009)

Scrolls in the Peranakan Tun Tan Cheng Lock's house (2 May 2009)

In the few months when Chinese merchants were stationed in Malacca, they got into liaisons with the local women. This led to the establishment of "branch families" where the wealthy male merchants fathered children with their local Malay wives. This happened not only in Malacca, but at every port of call where they conducted business activities, while they continued to maintain their "main family" in Fujian Province, China.

During the 15th century, the Malays were not yet Muslim by default. It was during this time that some began to embrace Islam, but many were Hindus and a large majority still did not follow any particular religion, or practised animistic traditions. It is probable therefore that the Malay women who married the merchant men come from families who are more open and accepting to the idea of their daughters marrying into a different culture. The financial and economic prowess of the husband were positive points that were taken into consideration.

During the 15th century, the Chinese merchant did not import Batak women as wives. This only happened later, in the 18th and 19th centuries, when the Malays have already fully embraced Islam. I will revisit this matter later on in this article.

The off-springs of these Chinese merchants saw their fathers only a few months every year. They grew up under the care of the Malay mothers who naturally spoke to them in Malay. But when the father came to call, they picked up a few Hokkien words that were added to their vocabulary. Thus, they established a creolized form of Malay, known today as Baba Malay, or Peranakan Malay.

It should be pointed out that in the 15th century, the Malays are not automatically Muslims. In fact by default many were Hindus. It was however during the 15th century, due to exposure to Indian Muslim merchants, that many began to convert to Islam. At that time there was no stigma for the Chinese merchants to take Malay women as wives, and these women adopted the Taoist tradition of their affluent Chinese husbands.

Entrance to the Cheng Hoon Teng temple (19 July 2009)

Entrance to the Cheng Hoon Teng temple (19 July 2009)

The half-blood Malay-speaking children of the Chinese merchants form the first generation of the Peranakan Chinese of Malacca. The majority had never seen their fathers' homeland, China. Unless they could prove themselves worthy to take on the fathers' trading business, this in all likelihood would pass down to their pure-blood Chinese half-brothers in Fujian.

The practice of establishing branch families continued even after the fall of the Malacca Sultanate. The presence of these localized Chinese is noted under Portuguese-administered Malacca, and later on, under the Dutch. In order to deal with this community, the Portuguese began the tradition of appointing a headman or penghulu, which the Portuguese called kapitan (after the Portuguese word capitão), to be the representative of the community, and this tradition was later passed on to the Dutch and the English.

The legends of Hang Li Po and Hang Tuah have now created dispute over their identities, whether Hang Li Po was truly a princess of the Ming court, and whether Hang Tuah was indeed Malay. While the Chinese eunuch Admiral Zheng He did visit Malacca, and the local ruler Parameswara probably did pay a courtesy visit to the Ming emperor Yongle, probably in Nanjing, whether Tun Perpatih Putih brought Hang Li Po to Sultan Mansur Shah is highly doubtful. If she existed at all, she might not have been a true-blood princess, but a beautiful maiden in the Ming imperial court who was hand-picked for the role of princess to be married to a far-away ruler, in this case, Sultan Mansur Shah of Malacca. Nevertheless, there is no doubt to the presence of Chinese people in the Malay peninsula during the 15th century.

Cheng Hoon Teng Temple, front façade (10 July 2005)

Cheng Hoon Teng Temple, front façade (10 July 2005)

It is said that Hang Li Po arrived with a contingent of five hundred ladies-in-waiting, and that the Malacca Baba Nyonya are the off-springs of the intermarriage of these ladies with local men. As the existence of Hang Li Po herself is disputed, the existence of these ladies-in-waiting is equally in doubt. It is more plausible that the Baba Nyonya of Malacca was the product of Chinese men who were merchants, who married local women.

There is good reason to believe that these merchants originated from Zhangzhou, which was a major international port of Fujian in the Yuan and Ming dynasties. Other possible ports may include Xiamen and Quanzhou. This is because a good majority of the loanwords in Baba Malay is Hokkien. In fact, the first Kapitan, or community leader, of Malacca (under the Portuguese administration), was Kapitan Tay Hong Yong (鄭甲) @ Kapitan Tay Kap @ Tay Kie Ki (1572-1617)11. He is said to have come from Zhangzhou, and is part of the Wave 1 settlers.

Tay Kap is noted in history as the first Kapitan of Malacca. He is also said to be the only Kapitan Cina under the Portuguese. Before that, the local Chinese community may also have appointed a wakil, or representative, to handle their affairs when dealing with the Malay sultans.

Eng Choon Association, front façade (10 July 2005)

Eng Choon Association, front façade (10 July 2005)

Subsequent Kapitans after Tay Kap included acculturated Chinese refugees from Wave 2, among them Kapitan Li Wei King (李為經) @ Li Jun Chang @Li Koon Chang @ Li Kap, who was part of the Ming resistance force against the Manchus. By then, Baba Malay had been established as the lingua franca, so Wave 2 Chinese settling in Malacca were expected to take up Wave 1 tradition, including learning Peranakan Malay.

The children of these Chinese branch families had mothers who were Malay. As a result of that, Malay became the mother tongue of these locally born, or peranakan, people. These people do not know of China as their homeland, but as a country far, far away which the majority have never visited. However, due to their interaction with their father, they picked up a limited vocabulary of Hokkien words. The resulting tongue is known today as Peranakan Malay while the people became known as the Baba Nyonya of Malacca.

(In similar fashion, the Eurasians of Malacca was a product of Portuguese soldiers who fathered children with Malay women, the off-springs speaking Cristang.)

Over the subsequent centuries, the Baba Nyonya of Malacca absorbed later immigrants of Waves 2 and 3, many of which became acculturated to the Baba Nyonya tradition. These later immigrants, particularly of Wave 3, may be able to trace one side of their ancestry to their China homeland, while the other side is Peranakan.

Photos on the wall, Tun Tan Cheng Lock's house (2 May 2009)

Photos on the wall, Tun Tan Cheng Lock's house (2 May 2009)

Arrivals of the Chinese of Wave 2

17th centuryThe Manchus breached the Great Wall of China in 1644. This led to the fall of Beijing. The last Ming ruler, the Chongzhen Emperor, committed suicide rather than face capture. Before doing so, he also gathered all members of the imperial household (aside from his sons) and killed them by his sword, with only 16-year-old Princess Chang Ping escaping death.

With the collapse of Ming rule in Beijing, the Manchus wasted no time in establishing the Empire of the Great Qing, also called the Qing Dynasty. Their troops began marching southwards, taking over China province by province.

Manchu troops arrived in Fujian province in 1651 where they faced resistance from Ming loyalist Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong). A massacre erupted in Zhangzhou in 1651-52. This massacre is one of the probable causes of a mass influx of Wave 2 refugees from Zhangzhou, some of whom ended up on the northern coast of the Malay peninsula (read Where does Penang Hokkien come from), from Prai northwards to Phuket and west to Medan. Meanwhile Koxinga was eventually defeated by the Manchu, and he escaped to Taiwan, where he in turn defeated the Dutch East India Company (1661-1662).

A façade at Hock Teik Cheng Sin Temple, George Town (26 July 2008)

A façade at Hock Teik Cheng Sin Temple, George Town (26 July 2008)

Once the Manchus consolidated their hold on Fujian Province, they continued their advance down the coast of China, into Guangdong and Hainan. Due to frequent strikes by coastal rebels, the Qing government issued a decree moving the population away from the coast. This was another probable cause of the mass influx of refugees from Fujian Province to populate various port settlements in Southeast Asia.

It should be noted that this second wave of immigrants would not have been possible if there were no on-going merchantile trade by the Hokkien seafarers. The receiving destinations would not have welcomed this sudden influx of refugees, had it not been that the Hokkiens have established a trading network and befriended the local rulers and chieftains, making it possible to relocate their entire family and property from China to various places in Southeast Asia, including the Malay peninsula.

They were the seed group, or pioneers. On the Malay peninsula, these refugees established themselves in places like Nakhon Si Thammarat (then known as Ligor), Songkhla and Pattani, and later moving south to Kuala Kedah. The language that they spoke was creolized to become the Penang Hokkien that we know today, while the customs that cooking style forms the basis of Nyonya food.

Why do we know so little about them? Because they were boat people. Just like the Vietnamese boat people of the 1970s, the majority packed up and left China without documenting their history. Many were possibly illiterate, so they could not write down what happened to them even if they wanted to.

Meanwhile, back in China, the Manchus also introduced their custom of wearing queues and the act of kowtowing before their officials. These customs faced resistance from the locals, and it is probably during this period that groups of Wave 2 refugees, rejecting a life under the Manchus, fled from Xiamen and Quanzhou, as well as perhaps Zhangzhou (if they had not left during the earlier massacre).

Between 1651 and 1682, when the Qing government eventually managed to take over Taiwan and incorporated it as a prefecture of Fujian province, there was no interaction between Fujian and the outside world.

The Fujian refugees of Zhangzhou resettled on the northern part of the Malay peninsula while those of Xiamen and Quanzhou resettled on the southern part of the peninsula. In Malacca, the southern group encounter the Baba Nyonya from Wave 1. While some of them intermarried and became acculturated into Wave 1 in Malacca, the others maintained their cultural differences as they populated settlements in the south including Klang, Malacca, Muar, Batu Pahat, Kluang and Pontian.

Unlike Wave 1, the Hokkien diaspora of Wave 2 included women and children. As they relocated in rather substantial numbers, they were able to reestablish themselves and continue the use of their Hokkien language in their adopted land, keeping to themselves and adopting loanwords from the Malays only when they find it necessary. Being far away from China however, required them to readapt their palate and cuisine, and they came up with their own style of fusion cooking, known today as Nyonya cooking.

Nyonya porcelain ware (8 October 2009)

Nyonya porcelain ware (8 October 2009)

The immigrants of Wave 2 experienced a period of isolation, when they were completely cut off from contact with China. As many of them were part of the resistance force against the Manchu invaders, returning to a Manchu-controlled China would spell certain death. During this period, they began to incorporate local words into their language, and local spices and ingredients into their cooking. Most of these loanwords are derived from Malay and also include words borrowed by Malay from Portuguese and other languages. (The Penang Hokkien Dictionary lists out many of these loanwords found today in Penang Hokkien.)

The refugees and their off-springs created their own microculture. Their food, which we know today as Nyonya, was the result of improvision. Cut off from the ingredients they were accustomed to from back home, they localize cuisine and their palate to what they could find around them. Among their noodle dishes, the oldest is probably laksa, made with rice noodles, as wheat is not available locally. These people were mostly illiterate, and they have no need to be literate. Unfortunately, as a result, they could not pass down their knowledge and stories in writing.

It was not until the Manchus have stabilized their grip on China, and peace resettled on Fujian Province, that the merchants were allowed to trade with Southeast Asia again. The illiterate pioneers provided the merchant class ready infrastructure in the port cities to establish themselves and their merchant guilds. However, the merchants, being the literate group, were able to record their own history. Thus, our knowledge of the history of the Chinese began when the merchants reestablish contact. Most of the clan associations in Penang, for example, were founded when the merchant group began trading with this region again. What happened before the arrival of the merchant group have been lost due to there being no one to record it down.

As the immigrants of Wave 2 originated from different cities in Fujian, they speak Hokkien that are similar but not fully the same. As such, there isn't a complete mutual intelligibility between the Hokkien spoken on the northern coast of the Malay peninsula from those of the southern coast. This mirrors the differences in Hokkien as spoken in Zhangzhou, Xiamen and Quanzhou.

These Wave 1 and Wave 2 immigrants were very different from the Wave 3 immigrants. Having never been exposed to Manchu rule, the men did not wear queues. They also adopted local form of dressing that is very different from the dressing of the later Wave 3 immigrants.

Kuan Im Teng, oldest Chinese temple in George Town, Penang (5 February 2013)

Kuan Im Teng, oldest Chinese temple in George Town, Penang (5 February 2013)

When Penang was established in 1786, many Hokkien settlers on the northern coast crossed over to resettle there. Similarly, when Singapore was established in 1819, many Hokkien settlers of Malacca, which was already passed from the Dutch to the English, also resettled there. In so doing, they brought with them their "Wave 2" Hokkien language. There is also a small remnant of Peranakans from Wave 1, speaking the Peranakan Malay, who relocated from Malacca to Singapore, but their numbers are much lower than those of the Hokkien-speaking Wave 2.

According to Dr Jean DeBernardi, in her book Penang - Rites of Belonging in a Malaysian Chinese Community, the leader of the initial group of Chinese immigrants to settle in George Town, Koh Lay Huan (? - 1826), was born in China.7 Koh Lay Huan was born in T'ung-an County, Zhangzhou Prefecture, Fujian Province.8.

Koh Lay Huan became involved with the Tiandihui, or Heaven and Earth Society 9, a fraternal organisation that the British viewed as a secret society, and hence coined the term "triad" to label it. The mission of Tiandihui was to overthrow the Manchu government, something which Koxinga tried and failed about a century before.

History was to repeat itself in that the Tiandihui also failed to dislodge the Manchus from their grip on China, and this time it was the turn of Koh Lay Huan and his men to flee. He arrived on the northern part of the Malay peninsula, where he was received by earlier Chinese settlers, descendants of Ming loyalists who fled generations earlier. Being a wealthy and educated man with experience in the trades of Southeast Asia, he easily assimilated himself into the local society. Koh established relationships with the local rulers by marrying their daughters. It is recorded that he married the daughter of the ruler of Nakhon Si Thammarat in 1821 8, and possibly a daughter of the ruler of Kedah as well.

Wat Mahathat, Nakhon Si Thammarat (13 January 2013)

Wat Mahathat, Nakhon Si Thammarat (13 January 2013)

Koh Lay Huan is believed to have first settled in Nakhon Si Thammarat, but later relocated to Kedah, where he reestablished himself at Kuala Muda. From this vantage point, he had his sights on the activity of Francis Light, who was busy looking for a site to establish a British naval base and trading port. When Light chose Penang Island, Koh Lay Huan immediately made contact. Recognizing the importance of receiving the enterprising Chinese into his newly establish town, Francis Light accepted Koh, who tend relocated to Penang bringing with him several boatload of settlers, both Chinese and Malays, from Kuala Muda.

Kuala Muda, Kedah (13 March 2005)

Kuala Muda, Kedah (13 March 2005)

The Chinese who arrived in Penang with Koh Lay Huan comprised both the newly arrived from Fujian as well as those who have settled in this region for a long time. The descendants of those who have been here since the 17th century had already created a creolised form of Hokkien with many Malay loanwords, and this creolised dialect became the main form of communication for the Chinese in Penang.

The founding of the Straits Settlements in 1826 helped to increase interaction between the Chinese people in Penang with that of Malacca and Singapore, resulting in the sharing of loanwords from their respective Hokkien dialects. Nevertheless, cuisine and other cultural influences, which each group developed separately, helped to set them apart.

Arrivals of the Chinese of Wave 3

18th centuryBy the mid-18th century, the Qing Dynasty of the Manchus has ruled China for two hundred years. By then, it has been severely weakened due to various reasons including droughts, corruption, inefficiencies and upheavals. The upheavals that caused the displacement of the Chinese people in Southern China is probably the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864), or more likely, the Punti-Hakka Clan Wars (1855-1867). These civil war brought great hardship and displacement of people in the southern provinces.

Coinciding with the hard times in China was a period of economic boom in the Malay peninsula. The discovery of large deposits of tin in the Larut district brought about the founding of Taiping, the first major town established by tin mining. Unlike the later towns, it was populated by immigrants brought in by Penang Hokkien merchants. As such, Penang Hokkien was introduced into Taiping as the lingua franca of the Chinese.

Chinese mining tools, Ngah Ibrahim's House, Kuala Sepetang near Taiping (31 January 2006)

Chinese mining tools, Ngah Ibrahim's House, Kuala Sepetang near Taiping (31 January 2006)

Meanwhile in China, Qing troops managed to defeat the rebels of the Taiping Rebellion. However, the massive civil warfare had not only caused a death toll of over 20 million people, it had also displaced millions more, with a large number of homeless and penniless refugees, many of whom Cantonese and Hakka. At the same time, new tin mines were being opened in Perak, Selangor and Negeri Sembilan, leading to the founding of towns such as Ipoh, Kampar, Gopeng, Kuala Lumpur and Seremban. These newly opened mining towns receive an influx of Cantonese and Hakka refugees who worked as tin mining coolies. Unlike the earlier group, this later group speak mostly Cantonese, and that language became the lingua franca of the later tin mining towns.

In the eyes of the British, all Chinese people looked the same. Many of the British officers were not able to speak the various Chinese languages. To differentiate between them, the British applied the term "Straits Chinese" to the group already living in Penang, Malacca and Singapore, realising that there were specific traits that set them apart from the new arrivals from China. The Straits Chinese themselves called these newcomers Sin3khek3, meaning "new guests". However, while Sin3khek3 refers to the Wave 3 immigrants, Straits Chinese refers to the Wave 1 and 2 immigrants.

Between the Straits Chinese and the Sin3khek3, there were certainly major differences that even the untrained eye could detect. The newcomers, having been fed Manchu culture for two hundred years, had shaved foreheads and were wearing queues. Although women immigrants later arrived, the first few batches of Wave 3 immigrants were almost all men who came as indenture labourers. Their intention was to work in Malaya for a specific period and then tnui1 Tng3 Snua1, meaning to return to China, to a supposed life of comfortable retirement and eventual demise. For many, this never happened, as the majority ended the rest of their lives in Malaya.

Devotees in Perak Tong, Ipoh (31 January 2006)

Devotees in Perak Tong, Ipoh (31 January 2006)

The application of the term "Straits Chinese" on the Wave 1 and 2 Chinese did not take into account their cultural and historical differences. The British did not differentiate whether they belong to the northern group centered on Penang, or the southern group centered on Singapore, or the Peranakan Chinese centered on Malacca. To the British, they are all Straits Chinese. The Straits Chinese themselves began to accept and adopt this term, as when they founded the Straits Chinese British Association in 1900 in Singapore and Malacca; and the Penang branch, which is now known as the State Chinese (Penang) Association, in 1920. The disservice of this blanket term is that it blurred the lines that differentiated the Wave 1 and 2 Chinese, and between those of Penang, Malacca and Singapore. As these groups interacted and intermarried among themselves, it became harder to tell them apart.

The Peranakan Chinese of Malacca grew up speaking Peranakan Malay. There is no record of them being given formal education under the Portuguese or Dutch. If it happened at all, it has long been forgotten. The Wave 2 immigrants settling on the northern coast of the peninsula spoke a Zhangzhou-based Hokkien while those settling on the southern coast spoke a Xiamen-based Hokkien dialect, known also as Amoy Hokkien. The majority were illiterate.

Until 1786, when the northern group relocated to British-established Penang, they were without formal education and largely illiterate. However, under the British, schools were established to teach them, initially in Malay, and later on in English. The Penang Free School was among the first. The Straits Chinese accepted British education as a means of written communication, and they became anglophiles, adoring all things English. The second half of the 19th century made them quite prosperous, and they flaunt their wealth by erecting mansions bearing English-sounding names.

In comparison, the Wave 3 immigrants arrived in Malaya penniless. A limited few went from rags to riches, but the majority remained poor. A Wave 3 coolie had little chance to marry into the Straits Chinese families, unless he could prove himself to be a man of great substance. The Straits Chinese preferred to marry among themselves, or to import brides from China. They often took on "lesser wives" who may come from their home province of Fujian (now that connection was reestablished) or from Batak housemaids and slaves. Chinese immigrants, from various cities in Fujian married into the Peranakan families and became acculturated, taking on their language and customs. They language they spoke would be Penang Hokkien if they were in Penang, Baba Malay if they married into a Wave 1 Malacca family, or southern Hokkien if they married into a Wave 2 family in Singapore and elsewhere on the southern part of the peninsula. This was the case with people like Cheong Fatt Tze, a Hakka Sin3khek3, who became one of the wealthiest man in Penang during his lifetime.

Unlike the 15th century, when the Wave 1 Chinese merchants freely took on Malay wives, by the 19th century the wealthy Straits Chinese as well as Sin3kheks3 wanting "lesser wives" often imported Batak and other non-Muslim native women from Sumatra. These lesser wives are often treated like concubines and semi-slaves within a household where the main wife (and not that commonly, second or third wife) serves as matriarch.

Hai Kee Chan, home of Kapitan Cina Chung Keng Kwee, leader of the Hai San (8 October 2009)

Hai Kee Chan, home of Kapitan Cina Chung Keng Kwee, leader of the Hai San (8 October 2009)

Over time, to meet the needs, women were also brought in from China to intermarry with the Wave 3 immigrants. However, unlike the Straits Chinese, the urge to tnui1 Tng3 Snua1 is strong with these Wave 3 immigrants. They rejected English education, and instead set up their own schools where their children were taught in their native tongues such as Hokkien, Teochew and Cantonese.

By the turn of the 20th century, the Qing government has been severely weakened by corruption and the unrelentless attack by various Western powers. This paved the way for the Chinese Revolution under Sun Yat Sen. Culturally, it was also the beginning of the modernization and Mandarinization of the local Chinese.

In response to the call of Sun Yat Sen, the Wave 3 Chinese began to cut off their queues and put on Western clothes. There was also a gradual conversion from the use of mother tongues to Mandarin in their schools. However, the anglophiles, most of whom are the Straits Chinese, continued to send their children to English schools and mission schools.

Fuk Tak Chi Museum, oldest Chinese temple in Singapore, now a museum (11 September 2010)

Fuk Tak Chi Museum, oldest Chinese temple in Singapore, now a museum (11 September 2010)

The change in education policies in the 1970s nationalized the English schools and mission schools. The Chinese, particularly the anglophiles, responded by turning away from the now nationalized English and mission schools, and began sending their children to Chinese schools. As a result, the Chinese society in Malaysia became more homogenous today than ever before.

The Chinese people has a history in the Malay peninsula spanning five hundred years or more. They arrived during various points in time, for trade purposes or when their homeland faced periods of turmoil. Though many speak Mandarin today, their mother tongues reflect their various periods of arrival. Under the British, 1786 until 1957, the various Chinese groups experienced great changes that eroded what we know about them, due to British biasness as well as lack of knowledge about them.

The history of the Penang Chinese goes back at least 350 years, to the time when Manchu invasion of Fujian brought the initial settlers. Much of this history has been lost to time, as the early settlers were illiterate and did not keep records of their arrivals. Nevertheless, through the re-examination of accounts, we are now able to piece together and appreciate their long-forgotten history.

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

Thian Hock Keng Temple, one of the most important Chinese temples in Singapore (8 July 2006)

Thian Hock Keng Temple, one of the most important Chinese temples in Singapore (8 July 2006)

Are you a Wave 1, Wave 2 or Wave 3 Malaysian Chinese?

The oft-repeated question I receive from many Malaysian Chinese has been whether their ancestors come from the Wave 1, Wave 2 or Wave 3. I can say with most certainly that the majority of us are of Wave 3. The Wave 1 and Wave 2 Chinese have never been large in numbers. Both Waves 1 and Wave 2 Chinese were overwhelmed by the arrival of the Wave 3 immigrants which greatly outnumbered the two aforementioned groups combined.The Wave 1 is almost certain of Hokkien ancestry. Wave 2 is predominantly Hokkien, with a sprinkling of Cantonese and Teochew. Wave 3 is predominantly Cantonese and Hokkien, with smaller numbers of Hakka, Teochew and Hainanese. In cities that pre-date tin mining, it is the Waves 1 and 2 that determine the lingua franca. Although cities such as Malacca, Penang and Singapore continued to receive immigrants in the 19th and 20th centuries, the newcomers acculturated themselves to the existing lingua franca, as well as adopted the local cuisine. In cities created by tin mining, the Wave 3 immigrants popularized Cantonese as the lingua franca.

If you are able to trace a grandparent, great-grandparent or great-great-grandparent who originate from China, you are most certainly a Sin3khek3, hence a Wave 3 Chinese. To be a Wave 2 Chinese, you need to prove that your ancestry goes back to the 17th century. To be a Wave 1 Chinese, you need to prove it going back to the 15th-17th centuries. Although many people may continue the Peranakan tradition, few are able to prove a lineage going back that far, so most of these Peranakan Chinese can be regarded as acculturated Peranakans.

What I have told you so far is subject to further revision, as and when I come across more material that help shed a light on my ancestors' distant past. I am writing this out of my own passion to understand the history of my ancestors as well as to correct some of the distortions that has been commonly accepted in the past. Thank you for reading. I hope that this article helps unlock your own interest in this subject.

Wikipedia References

Bibliography

- From the Mediterranean to the China Sea: Miscellaneous Notes, edited by Claude Guillot, Denys Lombard and Roderich Ptak, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, page 149

- Talk by Dr Tan Ta Sen on Peranakan - International Zheng He Society

- Sino-Malay Trade and Diplomacy from the Tenth Through the Fourteenth Century, by Derek Heng, Ohio University Press, page 133

- The Rise of Merchant Empires: LOng Distance Trade in the Early Modern World, by James D. Tracy, Cambridge University Press, page 405

- Connecting and Distancing: Southeast Asia and China, by Ho Khai Leong, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2009, page 11

- Sojourners and Settlers: Histories of Southeast Asia and the Chinese, edited by Anthony Reid, University of Hawaii Press, 2001

- The Chinese Diaspora: Space, Place, Mobility and Identity, edited by Laurence J.C. Ma & Carolyn L, Cartier, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2003

- Penang - Rites of Belonging in a Malaysian Chinese Community by Jean DeBernardi (2004, Stanford University Press)

- Koh Lay Huan, Wikipedia

- Tiandihui, Wikipedia

- Kapitan Cina of Malacca, Wikipedia

Learn Penang Hokkien with Memrise

Now you can use the most user-friendly tool on the web to learn Penang Hokkien. It helps you to listen, understand and memorise. Go to Memrise, and learn Penang Hokkien at your own pace.

Private Guided Tours of Penang

If you are seeking private guided tours of Penang, message Penang Tour Guides at penangtourguides@gmail.com and enquire with them. Buy, rent or sell properties in Penang

Buy, rent or sell properties in Penang

Do you have a property for sale or to rent out? Are you looking to buy or rent a property? Get in touch with me. WhatsApp me (Timothy Tye) at 012 429 9844, and I will assign one of my property agents to serve you. I will choose the agent for you, according to your property needs. So when you message me, provide me some details of what you need, whether to sell, to buy, to rent or to rent out, and what type of property, is it condo, apartment, house, shop, office or land. Latest updates on Penang Travel Tips

Latest updates on Penang Travel Tips

Map of Roads in Penang

Map of Roads in Penang

Looking for information on Penang? Use this Map of Roads in Penang to zoom in on information about Penang, brought to you road by road.About this website

Dear visitor, thank you so much for reading this page. My name is Timothy Tye and my hobby is to find out about places, write about them and share the information with you on this website. I have been writing this site since 5 January 2003. Originally (from 2003 until 2009, the site was called AsiaExplorers. I changed the name to Penang Travel Tips in 2009, even though I describe more than just Penang but everywhere I go (I often need to tell people that "Penang Travel Tips" is not just information about Penang, but information written in Penang), especially places in Malaysia and Singapore, and in all the years since 2003, I have described over 20,000 places.

While I try my best to provide you information as accurate as I can get it to be, I do apologize for any errors and for outdated information which I am unaware. Nevertheless, I hope that what I have described here will be useful to you.

To get to know me better, do follow me on Facebook!

Copyright © 2003-2025 Timothy Tye. All Rights Reserved.

Go Back

Go Back