Penang Hokkien Tone Sandhi for Beginners (28 February, 2004)

Penang Hokkien Tone Sandhi for Beginners (28 February, 2004)

When we speak in English or Malay, we often change the tone of the words to fit them into the sentence. We are so used to doing it that we might not even realise the changes that occur to the tone of words. And yet, when we learn a new language, we someone expect that the tone of the words are frozen and remain the same throughout a sentence. This misleading expectation makes learning a tonal language (a language where the tone governs the meaning) quite difficult. However, once we realise that we have been changing tones all along, in English and in Malay, and we can apply this to Penang Hokkien, then changing tones become second nature to us.

The tones in the following examples are according to how Malaysians pronounce English and Malay - non-Malaysians might pronounce these two languages by other tones, so my examples are based on the Malaysian context.

The grammatical name for changing tones is Tone Sandhi. In most languages, when we place two words together, the one in front changes its tone while the one behind remains the same.

Take for example "school bus". It comprises two words, "school" and "bus". If we were to place tone numbers against each word, they would look like this:

School4

Bus1

Placing them together, we form the following:

School1 bus1

Notice that the word "school4" has changed its tone to "school1" in order to fit in front of the word "bus1"? The original tone 4 in "school" has changed to tone 1.It works the same way in Malay. For example:

Ru1mah4

Ba3ha1ru4

When you put the word "ru1mah4" in front of "ba3ha1ru4", you get "ru1mah1 ba3ha1ru4".

Ru1mah1 ba3ha1ru4

The reason it is easy to ignore the tones in English and Malay is because most of the times, words follow a specific tone pattern. One syllable words usually (but not always) carry tone 4 in English and Malay (for example, cat4  , dog4

, dog4  , kuat4

, kuat4  , siap4

, siap4  ) As I've said, there are exceptions (i.e. bus1

) As I've said, there are exceptions (i.e. bus1  , yang3

, yang3  ) but because we ignore the existence of tones, we simply learn the word in its expected tone.

) but because we ignore the existence of tones, we simply learn the word in its expected tone.Words of two syllables in English and Malay usually follow a 1-4 tone pattern, for example ri1ver4

, pen1cil4

, pen1cil4  , ru1mah4

, ru1mah4  , can1tik4

, can1tik4  .

.Words of three syllables in English and Malay usually follow the 1-1-4 tone pattern in English and 3-1-4 tone pattern in Malay. For example, ex1er1cise4

, han1di1cap4

, han1di1cap4  , je3lu1tong4

, je3lu1tong4  , ba3ha1ru4

, ba3ha1ru4  .

.I am not saying that this applies in all cases, but in most, it certainly does. What we can do is to take what we already know (though have ignored) in English and Malay, and apply it to learning Penang Hokkien.

In our earlier lessons on Pronunciation and Intonation, we learned that in Taiji Romanisation of Penang Hokkien, each syllable can be pronounced in one of the four tones, 1, 2, 3 and 4. We also learn that there is a fifth tone, 33, which I said I will tell you more shortly. In this lesson, in a short while, we will get to know tone 33.

Morphemes

In the above examples, we have seen how words in English and Malay change their tones when we put them together. The word "school bus" if formed from two words, "school" and "bus". The words "school" and "bus" are in their most basic form - we can't further split it down. These basic, root words are known as morpheme.A morpheme can be one syllable, i.e. bus, or more than one, i.e. exercise. It's the same in Malay, i.e. kuat, or pokok.

This is true also for Penang Hokkien. Most morphemes in Penang Hokkien are one syllable long. In order to qualify as a morpheme, the syllable has to have a meaning, for example gau2

(clever), ciok3

(clever), ciok3  (to borrow), cu4

(to borrow), cu4  (to cook).

(to cook).If a syllable has no specific meaning, it is just sound, it is not a morpheme. Therefore, a morpheme can be a word in itself, but it can also be combined with other morphemes to form more words.

You can often identify the meaning of words based on the morphemes used to form them. When we put morphemes together, the front morpheme undergoes a tone change. This is called tone sandhi. If the word is formed from three morphemes, then the first two undergo tone sandhi. Basically, all morphemes sandhi except the last one. For example:

cu4

(to cook) plus ciak1

(to cook) plus ciak1  (to eat) becomes cu1ciak1

(to eat) becomes cu1ciak1  (cooking) (and not cu4ciak1

(cooking) (and not cu4ciak1  )

)Cu4, which was originally tone 4, has changed to cu1, tone 1, in order to fit in front of ciak1, to form cu1ciak1. As cu1ciak1 is a compound word, the two morphemes are written together.

thark1

(to read) plus chaek3

(to read) plus chaek3  (book) becomes thark3 chaek3

(book) becomes thark3 chaek3  (to read book) (not thark1chaek3

(to read book) (not thark1chaek3  )

)Thark1, which was originally tone 1, has changed to thark3, tone 3, in order to fit in front of chaek3, to form thark3 chaek3. As thark3 chaek3 are two separate words, the morphemes are written apart.

wah4

(I) plus boek3

(I) plus boek3  (want) plus khee3

(want) plus khee3  (to go) plus co3

(to go) plus co3  (to do) plus kang1

(to do) plus kang1  (work) becomes Wah1 boek1 khee1 co1kang1

(work) becomes Wah1 boek1 khee1 co1kang1  (I want to go to (do) work)

(I want to go to (do) work)In the above example, all the words change their tones except the final word (kang1). The morphemes are written apart except if they come together to form another word (co1kang1 = to work).

Rule of Tone Sandhi in Penang Hokkien

A morpheme in its original tone is said to be in the citation form. This is the tone of the words as listed in the Penang Hokkien Dictionary. Once it has undergone a tone change, it is in the sandhi form.Compared with the traditional forms of romanisation for Penang Hokkien (such as Church and Taiwanese Romanisation), the rule of tone sandhi for Penang Hokkien using Taiji Romanisation is fairly simple.

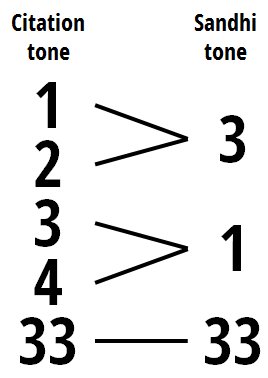

This is how it goes:

Morphemes which are originally tones 1 or 2 change to tone 3; morphemes which are originally tones 3 or 4 change to tone 1; morphemes which are originally tone 33 remain tone 33.

Morphemes of single-digit tones (1, 2, 3, 4) behave the same as one another - they all change tones from citation to sandhi form. Morphemes of tone 33 are unique - they sound like tone 3, but do not change their tone. So, they are written with tone 33 to differentiate them from morphemes of tone 3.

As a general rule of thumb, when you put two morphemes together, the one in front changes its tone. The four tones (1, 2, 3, 4) in the citation form change to just two tones in the sandhi form, namely tone 1 and tone 3. Morphemes of tone 33 are always written with tone 33, whether in citation or sandhi form, even though they sound the same as tone 3.

What I have explained above represents a very simplified explanation about the rules of tone sandhi in Penang Hokkien. As we progress in our learning, I will introduce how you would sandhi the words in sentences. Nevertheless, what you are learning here is a huge simplification over the traditional methods, which employ seven classes of tones, resulting in a very complex tone sandhi rule. I assure you that this simplification of the rules does not bring about a loss in meaning, and in fact, this methods helps readers identify the actual tone they are expected to pronounce each morpheme.

And now it's time to practise. As they say, practise makes perfect.

Practice 1: Writing

When two words are put together, the final syllable of the front word has to sandhi.Example

kang4 (river) + pni1 (side) = ? (river side)

Answer: kang1 pni1 (river side)

lor1li4 (lorry) + knia4 (child) = ? (small lorry)

Answer: lor3li1 knia4 (small lorry)

kong4 (to say) + wa33 (words) = ? (to speak)

Answer: kong1wa33 (to speak)

ang2 (red) + mor2 (hair) + tau33 (soybean) + iu2 (oil) = ? (localised Worchestershire sauce)

Answer: Ang3mor3 tau33iu2 (localised Worcestershire sauce)

Now your turn to try. Join the two words together and write them out with the right tone numbers.

1. kao4 (dog) + knia4 (child) = ? (puppy)

2. Pe3nang4 (Penang) + lang2 (person) = ? (Penangite)

3. jip1 (to enter) + mui2 (door) = ? (to enter door)

4. char4 (to stir fry) + luan33 (noisy) = ? (to disturb)

5. kau3ie4 (chair) + kha1 (leg) = ? (leg of the chair)

Practise 2: Listening

1. lau3 (to leak) + chooi4

(to leak) + chooi4  (water) = lau1chooi4

(water) = lau1chooi4  (leaking)

(leaking)2. ciau4

(bird) + knia4

(bird) + knia4  (child) = ciau1knia4

(child) = ciau1knia4  (baby bird)

(baby bird)3. thor2

(ground) + tau33

(ground) + tau33  (nut, bean) + thng1

(nut, bean) + thng1  (soup) = thor3tau33thng1

(soup) = thor3tau33thng1  (groundnut soup)

(groundnut soup)4. au33

(back) + boey4

(back) + boey4  (tail) + lor33

(tail) + lor33  (road) = au33boey1lor33

(road) = au33boey1lor33  (back alley)

(back alley)5. am1meh2

(night) + pan1

(night) + pan1  (class) = am1meh3 pan1

(class) = am1meh3 pan1  (night class)

(night class)

Exercise 1: Writing

The answers is not provided. Finish the exercise and send your answers to me (mentioning that it is for the lesson on Tone Sandhi), and I will provide you the right answer. You can contact me here or by PM on Facebook.1. or1 (black) + pan4 (board) = ? (blackboard)

2. hee1 (show) + tai2 (stage) = ? (cinema, theatre)

3. thor2 (earth) + kha1 (leg) + chu3 (house) = ? (landed property)

4. ciu4 (wine) + au1 (glass) = ? (wine glass)

5. lor33 (road) + teong1 (middle) = ? (middle of the road)

6. ang2 (red) + cap1 (ten) + ji33 (word, character) + chia1 (car, vehicle) = ? (ambulance)

7. knia4 (child) + soon1 (grandchild) = ? (descendants)

8. hoay4 (fire) + chia1 (car, vehicle) + cam33 (station) = ? (train station)

9. cap1 (ten) + gor33 (five) + meh2 (night) = ? (15th evening of Chinese New Year)

10. ang3mor3tan1 (rambutan) + hnui2 (plantation) = ? (rambutan plantation)

Exercise 2: Listening

For each question, choose the right answer by listening.1. sna1

(clothes) + tu2

(clothes) + tu2  (cupboard) = ? (wardrobe / cupboard for clothes)

(cupboard) = ? (wardrobe / cupboard for clothes)A.

B.

C.

D.

2. bor4

(wife) + knia4

(wife) + knia4  (child, children) = ? (family)

(child, children) = ? (family)A.

B.

C.

D.

3. bee4

(rice) + ang3

(rice) + ang3  (barrel) = ? (rice barrel)

(barrel) = ? (rice barrel)A.

B.

C.

D.

4. thau2

(head) + chiu4

(head) + chiu4  (hand) = ? (foreman)

(hand) = ? (foreman)A.

B.

C.

D.

5. kiam2

(salty) + ak3

(salty) + ak3  (duck) + nui33

(duck) + nui33  (egg) = ? (salted duck egg)

(egg) = ? (salted duck egg)A.

B.

C.

D.

6. char4

(to stir fry) + koay1teow2

(to stir fry) + koay1teow2  (flat rice noodle) = ? (char koay teow)

(flat rice noodle) = ? (char koay teow)A.

B.

C.

D.

7. lau33

(old) + lang2

(old) + lang2  (people) + keng1

(people) + keng1  (building) = ? (old folks' home)

(building) = ? (old folks' home)A.

B.

C.

D.

8. sin3 cnia1

(new year) + sna1

(new year) + sna1  (clothes) = ? (new year clothes)

(clothes) = ? (new year clothes)A.

B.

C.

D.

9. nyau2

(goat) + bak3

(goat) + bak3  (meat) + thng1

(meat) + thng1  (soup) = ? (mutton soup)

(soup) = ? (mutton soup)A.

B.

C.

D.

10. am3

(dark) + bong1

(dark) + bong1  (touch) + bong1

(touch) + bong1  (touch) = ? (pitch black)

(touch) = ? (pitch black)A.

B.

C.

D.

Language Learning Tools

Use the following language learning tools to learn Penang Hokkien!Learn Penang Hokkien with uTalk

This app opens the door to over 150 languages.Return to Penang Hokkien Resources

Copyright © 2003-2025 Timothy Tye. All Rights Reserved.

Go Back

Go Back