Understanding the History of Penang Hokkien (21 August 2004)

Understanding the History of Penang Hokkien (21 August 2004)

Penang Hokkien is over three hundred years old. It is older than Penang itself. The language is believed to have been brought to this region following the fall of the Ming Dynasty (1644), after the takeover of Fujian Province by the Manchus, and in particular, after the massacre that took place in Zhangzhou in 1651-52, which is believed to have caused an exodus of Hokkien diaspora throughout Southeast Asia.

Fleeing their homeland, the Hokkien refugees relied on their ready knowledge of merchantile sea-routes to re-establish themselves all over Southeast Asia, or Nanyang, as it was known to them.

The ancestors of Penang Hokkien are believed to have re-established themselves in southern Thailand, in the then Kingdom of Kedah, which covered a larger area than the present State of Kedah. For at least one generation, the immigrants were cut off from their ancestral homeland. Living in isolation, they began to adopt properties of local culture, borrowing many Malay loanwords as well as elements of Malay and Siamese cooking, to create the distinctive culture of their own, which we know today as Penang Nyonya.

Refugees from different parts of Fujian Province resettled in various locations along the Malay peninsula, as they did elsewhere in Southeast Asia. As a result, the Hokkien spoken in Penang is different from that in Klang and Muar, and is again different from the Hokkien spoken elsewhere in the region. After links with China was re-established, the region continued to receive Chinese immigrants, particularly Ming loyalists who continued to wage wars against the Qing government, and were forced into exile when they were defeated.

Among the later arrivals was Koh Lay Huan, who was born in Zhangzhou, Fujian Province, and was also a prominent member of the Tiandihui, or Heaven and Earth Society, a secret society plotting to bring down the Qing Dynasty. When that failed, he fled to southern Siam, where he became a prominent figure in Nakhon Si Thammarat and later Kuala Muda. When Francis Light founded the British trading port in Penang in 1786, Koh led a group of Chinese and Malays to relocate to the island. In so doing, he introduced Penang Hokkien to the island.

Over the course of the 19th century, Penang continued to receive Chinese immigrants. In addition to Hokkien immigrants, there were also Cantonese, Teochew, Hakka and other subgroups. Though they spoke their own dialect among themselves, they accepted Penang Hokkien as their lingua franca, the language they use to communicate among themselves.

In the mid-19th century, the Taiping Rebellion displaced millions of people in China. It coincided with the Industrial Revolution in Britain, which brought about a surge in demand for tin. At the same time, tin ore was discovered in vast quantities in many mining fields in Perak, and later on in other states along the peninsula. With that came an influx of Hokkien and later on, Hakka and Cantonese miners into the peninsula. The earliest batch of miners were indentured laborers sponsored by Hokkien investors in Penang. They established the mines in Larut, leading to the use of Penang Hokkien as the eventual lingua franca of towns there such as Taiping. In comparison, later mining towns were established by the Hakka and Cantonese miners, and these adopted Cantonese as the lingua franca.

The Chinese population that have already established themselves in Penang, Malacca and Singapore prior to the large influx of the mid-19th century called themselves the Lau33khek3, meaning the "old timers". They refer to the new comers as Sin3khek3, meaning "new guests". To differentiate between the two, the British coined the term "Straits Chinese" to refer to the Lau33khek3, though many of the newcomers settling in the Straits Settlements also acculturated themselves to the customs of the Lau33khek3, and began calling themselves Straits Chinese as well.

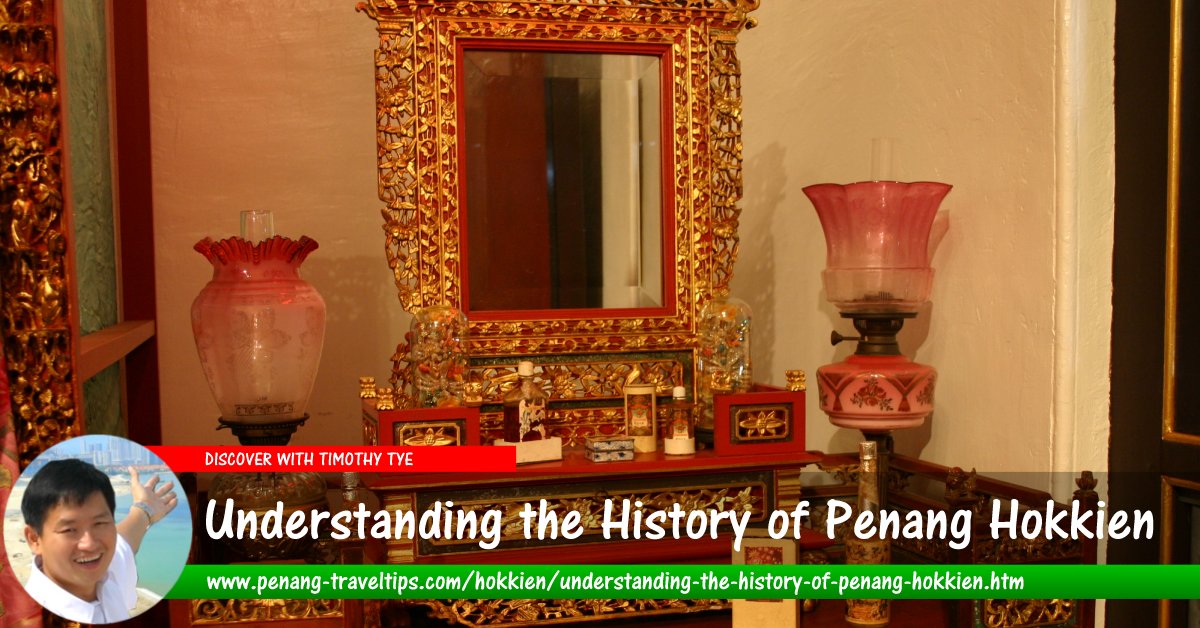

The cultural characteristics of the Lau33khek3 include their cooking style, their dressing, and most importantly, their language, a creolized form of Hokkien that borrows Malay loanwords and spelling convention from Malay and English. In comparison to the largely penniless Sin3khek3, the Straits Chinese form the upper middle class of the Chinese society in Penang. Many of them are English educated, and they send their sons to English schools, in order to take on clerical positions in British firms. Their homes reflect an eclectic fusion of East and West. They have refined tastes, and their homes are filled with Nyonya porcelain (made in China specifically for local use), European enamel wares, glass vases, jewellery and furniture. The majority of the Straits Chinese do not learn to write Hokkien, they were educated in English, and pledged allegiance to Queen Victoria, and they prided themselves in speaking the Queen's English. But at home they continued to speak Penang Hokkien.

Until now, Penang Hokkien remained an oral form of communication. Hokkien itself was largely a spoken language, though a small number of the immigrants - particularly the upper crust merchant class and priest class - learned to write Hokkien using Classical Chinese. This is the literary form of Chinese used for almost all formal communication in China until the early 20th century. However the literary register often differ significantly from the colloquial. It was a form of communication of the upper crust, and needless to say, the majority of the Hokkiens remained illiterate. Moreover, written Hokkien never developed to a stage comparable to the written form of Cantonese and Mandarin5. Various expressions in Hokkien are not associated with Chinese characters in Vernacular Chinese, and so some of the Hokkien words could not be written as there were no Chinese characters assigned to them.

Until present-time, the most serious attempt to romanize Hokkien was carried out by Western missionaries in the 19th century. It is called by various names including Romanized Amoy Vernacular and Church Romanisation, to name two. This romanisation system is known in Hokkien itself as Peh-oe-ji, or POJ for short. The Southern Min language, or Min Nan, for which this romanisation system was developed, is called Bân-lâm-gú, literally, "Southern Fujian language"7. The name Peh-oe-ji means "vernacular writing"6, a term many regard as misleading, as both the literary and colloquial registers of Southern Min appear in the system, not just the "vernacular", as the term seems to suggest.

The Taiwanese Romanization System for Hokkien, also called Tai-lo, is derived from Peh-oe-ji. However, when a writing system is created for Penang Hokkien, a wholesale adoption of Peh-oe-ji was rejected due to glaring cultural incompatibility. Instead, a writing system was created for Penang Hokkien that borrows elements from Peh-oe-ji, with characteristics of English and Malay orthographies. This writing system preserves the spelling of commonly used words in Penang Hokkien, particularly those related to food and people's surnames. Observations were made on how the locals intuitively spell, and these are adopted into the writing system. The resulting writing system is called Taiji Romanisation for Penang Hokkien. This writing system is intended not only to write down the spoken language, but also develop it into a written form of communication, by clearing away ambiguities that cloud the spoken form, due to the presence of numerous homographs.

Penang Travel Tips' Learn Penang Hokkien is the most comprehensive free online course for learning Penang Hokkien. It covers every aspect of the language. Users of Penang Hokkien benefit from the online dictionary with audio output listing over three thousand commonly used words. The mission of this website is to make Penang Hokkien easy to learn for all people, whether they are tourists, expatriates or locals.

Those who already speak Penang Hokkien as their mother tongue are encouraged to learn to write the language using this system, so that they can communicate with their loved ones and friends in writing. Efforts are also on the way to make teach Penang Hokkien in Malay and other languages, so that all Malaysians have the opportunity to learn Penang Hokkien.

Read also Penang Hokkien Vocabulary, Penang Hokkien main page

Language Learning Tools

Use the following language learning tools to learn Penang Hokkien!Learn Penang Hokkien with uTalk

This app opens the door to over 150 languages.Return to Penang Hokkien Resources

Copyright © 2003-2025 Timothy Tye. All Rights Reserved.

Go Back

Go Back